Policy and planning tools for healthy corner stores.

This blog posting is a quick introduction to some research Tufts student Leah Lazer and I are carrying out. The project will focus on policy and planning tools and techniques that cities can use to promote the sale of fresh, healthy food at corner stores in low-income and minority communities in order to increase food access and food security for local residents. Based on a literature review, review of planning and policy reports, news articles and in-person interviews, we will examine which tools work best within city-specific contexts of budget constraints, density and zoning, pre-existing infrastructure, the characteristics of the target beneficiaries, and more.

This blog posting is a quick introduction to some research Tufts student Leah Lazer and I are carrying out. The project will focus on policy and planning tools and techniques that cities can use to promote the sale of fresh, healthy food at corner stores in low-income and minority communities in order to increase food access and food security for local residents. Based on a literature review, review of planning and policy reports, news articles and in-person interviews, we will examine which tools work best within city-specific contexts of budget constraints, density and zoning, pre-existing infrastructure, the characteristics of the target beneficiaries, and more.

The Problem

Poor food access in low-income communities (food deserts) can be explained by a complex interaction of many economic, social, political and historical factors that have disadvantaged certain groups and concentrated them in areas where, among other problems, distance and price may limit their ability to obtain fresh, healthy, affordable, culturally appropriate food. However, these same areas are food swamps; often having an abundance of cheap, calorie-rich, nutrient-poor foods, frequent consumption of which creates widespread health problems for the consumer.

Two main structural causes have persisted over time to create urban environments where low-income and minority groups suffer from food insecurity: the devaluation of urban capital and institutional racism. McClintock (2011, p. 95) argues that historical patterns of urban decay consist of developing infrastructure and industrial areas during economic booms, and abandoning them in economic downturns. In these landscapes, food access declines as a result of poverty, poor infrastructure and an inhospitable environment for new businesses that might sell healthy food. According to Billings and Cabbil (2011), these inner-city landscapes are populated by the marginalized, disadvantaged members of society who have for generations been victims of institutionalized racism that contributes to a host of inequalities, including food insecurity.

The direct causes of food insecurity for low-income populations are more tangible. Because of the urban decay processes described above, Raja et al. (2008) found that few supermarkets and grocery stores are located in low-income or minority neighborhoods, even though they are the preferred source of fresh, healthy, affordable food for most people. The food sources that are located nearby, often fast food restaurants, sell cheap, calorie-rich but nutrient-poor food. Corner stores or convenience stores are often plentiful in these areas as well, but sell mostly unhealthy food, liquor or charge more than supermarkets for healthier options. This means that residents of these areas must travel long distances and spend extra time to procure healthy, affordable food. This is exacerbated by the fact that many can’t access a car, and their neighborhoods are often poorly served by public transportation.

Even if they could physically access healthy food sources, many people live in poverty that denies them economic access to food. According to Kumayika and Grier (2006), federal programs that help with food access, like SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) and WIC (Women, Infants and Children), provide financial assistance to food insecure families. However, these often do not cover the full cost of food, and do not address the underlying causes of hunger. Finally, Guthrie and Variyam (2007) said that many people haven’t had sufficient education about diet, nutrition, fitness and health to take full advantage of healthier choices when they are available, or might not know how to prepare nutritious meals from whole ingredients.

According to Chang et al. (2009) and MassCHIP (2010), lack of access to healthy food in low-income and minority neighborhoods has many negative consequences, both immediate and long-term. Diets based on food that is calorie-rich but innutritious leads to higher rates of obesity and its associated health effects, including type-II diabetes and cardiovascular disease. It can also lead to limited mobility and decreased productivity. Food insecurity can also be a serious psychological stressor.

Policy and Planning for Healthy Corner Stores

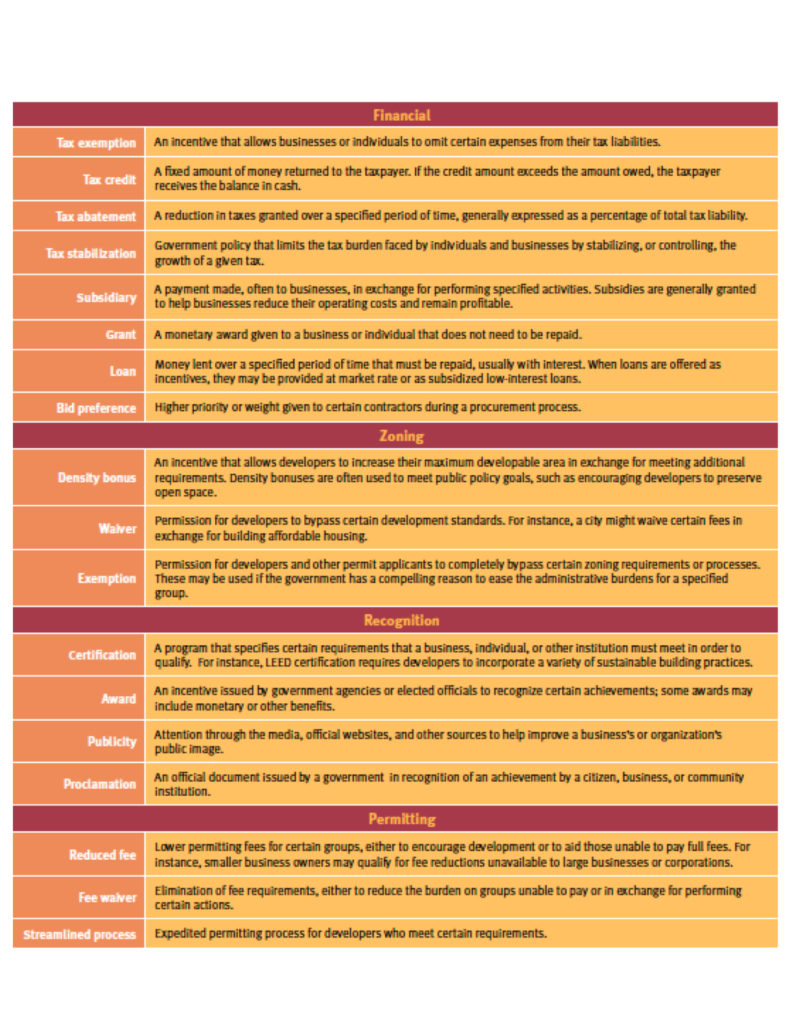

There are many options available to planners and policy-makers to increase the sale of healthy food in corner stores. Fry (2012, p. 10) argues that cities could use financial incentives by providing money to businesses to buy new equipment or offset operating costs. They could reduce regulatory and administrative burdens by creating exceptions to zoning, density, and permitting requirements for stores selling healthy food. They could also pass legislation that requires stores to sell a certain quantity of healthy food, or create a grant or government office that focuses on supporting non-governmental initiatives to improve food access.

Table 1 Summary of possible policy and planning tools to encourage healthy corner stores.

Raja et al. (2008) said that empowering local corner stores and small grocery stores to sell healthy food makes use of existing food retail infrastructure, lowering the time frame and space requirement needed to bring healthy options to a neighborhood. Since many stores are owned by local residents, they can be more attuned and responsive to the cultural and other preferences and dietary patterns of the community, compared to a large supermarket or a chain. Finally, encouraging residents to purchase food within their neighborhood can stimulate the local economy.

Why Policy and Planning Tools?

Combating food insecurity with policy and planning tools has the potential to create more beneficial and enduring change in local food systems, compared to other more laissez-faire approaches. Many laissez-faire initiatives are based on small-scale partnerships between city governments, local non-profits and a number of corner stores. While these partnerships have made significant progress in several cities, they are contingent on the civic-mindedness, long-term commitment, and risk-taking of participating corner store owners, making them an inherently less permanent solution. A well-researched and appropriately structured policy or planning approach would immediately and continuously affect all relevant businesses, requiring less ongoing support and funding while paying dividends in terms of local access to healthy and culturally appropriate food.

Which Tools?

The most challenging and crucial step in the planning and policy-making process for healthy corner stores is selecting the most effective mix of tools for a particular area. Fry (2012) said that to make these decisions, policy-makers consider whether to use regulations or incentives, the cost of the legislation compared to their budget and staff hours, how to best target the intended vendors or consumers, the neighborhood density and zoning laws, and more.

Current Examples

Several cities have already taken a policy or planning approach to healthy corner stores. According to Fry (2012), the Minneapolis City Council passed a staple food ordinance in 2008 requiring Minneapolis corner stores to carry five varieties of perishable produce in their stores. San Francisco has legislated the definition of a “healthy food retailer” to be stores with at least 35 percent of the selling area containing fresh produce and no more than 20 percent of the area having tobacco or alcohol for sale. New York City offers tax abatement or stabilization to grocery stores in food deserts with at least 6,000 sq. ft. of grocery, at least 30% of which must be devoted to perishable goods, and waives some of their parking requirement. Newark, NJ offers incentivizing grants and Denver, CO allows developers to add four sq. ft. of mixed-use space for every one sq. ft. of food retail space in new developments.

Our Research and Next Steps

So far, the research has consisted of gathering and reviewing literature and refining our research question. The next step will be interviewing employees of city government agencies or non-profit organizations involved in healthy corner stores initiatives, to learn about the choice of policy and planning tools, implementation processes and the predicted (or actual) effects of their projects.

References

- Billings, David, and Lila Cabbil. “Food Justice: What’s Race Got To Do With It.”Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Context 5.1 (2011): 103-12. Project Muse. Web. 14 Nov. 2012.

- Chang, Virginia W., Amy E. Hillier, and Neil K. Mehta. “Neighborhood Racial Isolation, Disorder and Obesity.” Social Forces 87.4 (2009): 2063-092. Print.

- Fry, Christine. Putting Business to Work for Health: Incentive Policies for the Private Sector. Page 10. ChangeLab Solutions, 2012. Web. 15 Nov. 2012.

- Kumanyika, Shiriki Kinika, and Sonya Grier. “Targeting Interventions for Ethnic Minority and Low-Income Populations.” The Future of Children 16.1 (2006): 187-207. Print.

- McClintock, Nathan. “From Industrial Garden to Food Desert: Demarcated Devaluation in the Flatlands of Oakland, California.” Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class, and Sustainability. By Alison Hope. Alkon and Julian Agyeman. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2011. 94-95. Print.

- “Our Partners.” Healthy Corner Stores Network. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Nov. 2012. <http://www.healthycornerstores.org/>.

- Raja, S., Ma Changxing, and P. Yadav. “Beyond Food Deserts: Measuring and Mapping Racial Disparities in Neighborhood Food Environments.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 27.4 (2008): 469-82. Print.

- USA. United States Department of Agriculture. Economic Research Service. Nutrition Information: Can It Improve the Diets of Low-Income Households? By Joanne F. Guthrie and Jayachandran N. Variyam. 29.6. 2007. Web. 18 Nov. 2012.

- USA. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. MassCHIP: Massachusetts Community Health Information Profile. Cardiovascular Health Report for Boston. 2010. Web. 16 Nov. 2012.

- USA. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. MassCHIP: Massachusetts Community Health Information Profile. Race/Hispanic Ethnicity Report: Health Risk Factors (BRFSS a) for Boston. 2010. Web. 16 Nov. 2012.

- USA. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. MassCHIP: Massachusetts Community Health Information Profile. Race/Hispanic Ethnicity Report: Mortality Data for Boston. 2010. Web. 16 Nov. 2012.

- USA. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. MassCHIP: Massachusetts Community Health Information Profile. Socio-demographic Standard Report for Boston. 2010. Web. 16 Nov. 2012.

Great topic!

Do you Phil Brown at Northeastern? I just read that he did some work in Providence bringing fresh produce to convenience stores.

I do Ann. I’ll check his work out. Thanks!