Storying institutions: Understanding why things are as they are.

Stories are everywhere. We tell stories about who we are, stories about other people and stories about our past. We read stories and watch them on our screens. We even use stories as professionals, students, and academics in planning and policymaking, although they aren’t always acknowledged as such. Storytelling and story-listening are important both because they are happening all around us, whether we realize it or not, and because stories can lead to change. In particular, they can help lead to equitable and just change.

Stories are everywhere. We tell stories about who we are, stories about other people and stories about our past. We read stories and watch them on our screens. We even use stories as professionals, students, and academics in planning and policymaking, although they aren’t always acknowledged as such. Storytelling and story-listening are important both because they are happening all around us, whether we realize it or not, and because stories can lead to change. In particular, they can help lead to equitable and just change.

Stories can take various forms. The stories we’re most used to telling and hearing are personal narratives—stories told at the individual level that help explain who we are and where we come from. Yet there are other stories that operate on the same principles, but at a larger scale. These institutional stories are the narratives that explain how the world works the way it does, through the examination and unfolding of historical processes. Institutional stories are institutional on two levels. First, they explain established ways of organizing society (such as government). Second, they are institutionalized, accepted as the way things are and ingrained within the way we understand society. Institutional stories are historical narratives that explain a neighborhood or a city in one particular way, although other institutional stories can contest the dominant story and shed light on different understandings.

Institutional storytelling is not a term that is used very often, but it’s not a completely unfamiliar concept. The idea of metanarrative, for example, can help describe institutional storytelling. Most storytellers focus on micronarrative—individuals’ stories, personal lessons, and small details. Metanarrative, on the other hand, takes a step back and considers larger lessons and trends (Sandercock 2003). A similar idea is that of narrative foreground and background. All narrative is made up of the story that takes place in the foreground, in front of us, full of rich details, as well as the larger background that influences the events of the narrative (Mandelbaum 2003). While it would be impossible to tell a story centered solely on background, institutional storytellers focus on linkage: bringing some of the background into the foreground often with profound effects as we illustrate below. Perhaps then, these ‘backgrounds’ are places planners and policymakers should occupy more often? The background of cities and neighborhoods is every bit as important as the foreground of present day realities, the usual habitat of planners and policymakers. The background tells us about equity and justice: why certain groups of people face poverty, why some cities are gentrifying, and why some neighborhoods lack access to fresh food.

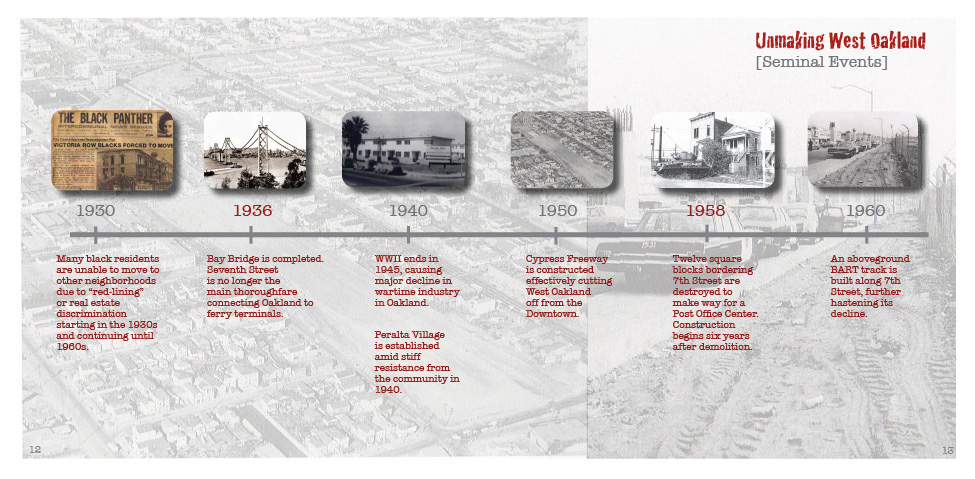

Scholars such as McClintock (2011) have provided excellent examples of stories full of background, but at the same time they shed critical light on contemporary socio-spatial processes and inequalities. Using the lens of Urban Political Ecology which is particularly good at revealing ‘the background’, McClintock tells the story of Oakland, California, exploring the “forces that have hewn the urban landscape into a crude mosaic of parks and pollution, privilege and poverty, Whole Foods and whole food deserts” (p90). By tracing out racist policies like bank redlining, yellowlining, racial covenants and federal housing subsidies, he shows that food deserts in Oakland don’t exist simply because of some ‘market abnormalities and imperfections’ or because people in the flatlands don’t want to eat healthy food. McClintock’s incisive storytelling shifts the conversation away from blaming the victim (through foregrounding the ‘behavioral’ problems of low income and minority groups), to revealing the background causes namely structural racism and “previous cycles of capital accumulation and devaluation, a palimpsest of building, decay and renewal” (p94).

In effect, McClintock is foregrounding the background to great effect. Even for people who suspect such a sordid history, the story he tells profoundly clarifies the structural racism that shapes Oakland’s current landscapes. While he may not call his narrative an institutional story, it certainly is just that. McClintock’s work, like others’, combats the idea that the consequences of policies and plans are natural rather than a product of human decisions (Raadschelders 2010). They give us, as planners and policymakers, the power to both imagine and ultimately fashion policies and plans that can deliver equitable and just change.

Despite the power of storytelling, there’s not much research about institutional stories and equity and justice in the urban and environmental policy and planning professions. There is however, some research into what storytelling in practice looks like in other urban professions. Banks (2012) covers the use of storytelling as a tool for equity in the health care system. For her stories are ways to understand how policies impact individuals as well as collective groups, and to explore unequal distribution of policy effects. She notes a lesson for institutional storytellers: “Storytelling facilitates emancipatory knowing, the ability to notice injustices or ‘what is wrong with the picture’ and to find creative means to correct social injustices” (p396). By critically examining the larger stories we’re a part of, we’re better able to see broader trends caused by institutionalized policies and behaviors that are unjust.

Dickinson’s (2012) work on storytelling and environmental racism in the context of Critical Race Theory offers a similar angle. She says stories “allow readers to be inserted into the lived realities of those most affected by a racialized society and expose the ridiculousness, irrationality, and dire implications of racism” (59). She calls upon the predictive power of stories. Historical stories at both the individual and institutional level show, for example, that racism is real and influential; therefore, we can predict that racism will continue to influence the future.

Clearly, institutional storytelling has a place in policy and planning. But we need examples within planning and policymaking practice. Institutional storytelling can’t be limited to planning historians and planning theorists when it has so much potential. Planning practitioners stand to capture all of the benefits of institutional storytelling if they choose to embrace it as a tool for justice.

Few realize however, that planners are always telling stories through their interactions with agencies, community-based organizations and neighborhood residents, as well as through the texts they produce. In other words, planning is storytelling. When a planner writes a comprehensive plan for his/her city, s/he is telling a very particular story about that city, which will have very particular consequences for zoning and other policies. When a planner holds a public meeting about a new community garden, s/he inevitably frames it as a story, perhaps claiming the city is drawing on a long tradition of gardening, or framing gardens as a way to improve poor access to healthy foods.

This second example demonstrates that storytellers can also knowingly use storytelling as a way to convince others (Van Hulst 2012). We don’t just passively and unwittingly tell stories—we use them to persuade and to play on emotions. Stories are, after all, often much more captivating than other kinds of information (note how political candidates always have a story about a named person that illustrates the point they’re making). The planner holding the community garden meeting has a better chance of gaining support if s/he can present a story that resonates with community members, or that includes strands of listeners’ own stories. And to be most effective (at least as far as equity is concerned) s/he should also understand the privileged positionality of the planner and his/her role as a storyteller by making space for others’ stories (Eckstein 2003, Goldstein et al 2003). At that same community meeting, the planner’s own story may steamroll the dozens of other stories in the room. Perhaps most of those people disagree with the planner, and want more playgrounds for their children rather than a garden.

The challenge of making institutional stories work for urban and environmental policy and planning is important and, at this point in time, innovative. Stories give voice to the silenced, they work toward inclusive cities and can address racism, classism and sexism head on. Institutional storytellers can strive to collect group stories to craft into large narratives. They can ask themselves which institutional story is being told and which stories are being left out. They can challenge the dominant story of why things are as they are and explore alternative explanations that include multiple voices that may change the direction of decisions and actions (see Incomplete Streets blog entry). The question then is, if institutional stories represent such a fertile ground for creating change, why aren’t they a bigger part of our planning/policymaking conversation?

The new generation of planners and policymakers could and should reinvigorate storytelling. Storytelling is arguably on everyone’s minds these days, as technology makes it easier to broadcast films and podcasts around the globe, and Internet memes reach anyone who’s plugged in. Students need to keep the momentum going, doing story research and incorporating it into the beginnings of their own practice since they are ideally placed to connect storytelling trends to real-life policy and planning. Meanwhile, academics have done a lot of work around storytelling, but there’s a lot left to do. Many researchers have written about the power of stories, particularly personal and ethnographic stories, but not many have identified institutional stories as a way to effect change. Even as researchers look more deeply into institutional stories, they also need to link research to practice. Universities are one obvious place to connect academics, researchers, and budding practitioners, and may be just the catalyst needed increase the storying of our institutions.

Kim Etingoff and Julian Agyeman

Kim Etingoff is a graduate student at Tufts University pursuing an MA in Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning.

References

Banks, JoAnne (2012). “Storytelling to access social context and advance health equity research.” Preventive Medicine 55: 394-397.

Dickinson, Elizabeth (2012). “Addressing Environmental Racism Through Storytelling.” Communication, Culture, & Critique 5: 57-74.

Eckstein, Barbara J. (2003) “Making Spaces: Stories in the Practice of Planning.” In Story and Sustainability, edited By B.J. Eckstein and J.A. Throgmorton. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Goldstein, Bruce Evan, et. al. (2003). “Narrating Resilience: Transforming Urban Systems Through Collaborative Storytelling.”Urban Studies 1-19.

Mandelbaum, Seymour J. (2003) “Narrative and Other Tools.” In Story and Sustainability: Planning, Practice, and Possibility for American Cities, edited by B. J. Eckstein and J. A. Throgmorton. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

McClintock, Nathan (2011) “From Industrial Garden to Food Desert.” In Cultivating Food Justice, edited by Alison Hope Alkon and Julian Agyeman. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Raadschelders, Jos C. N. (2010). “Is American Public Administration Detached From Historical Context?” The American Review of Public Administration 40 (3): 235-260.

Sandercock, Leonie (2003). “Out of the Closet: The Importance of Stories and Storytelling in Planning Practice.” Planning Theory & Practice 4, no.1: 11-28.

Van Hulst, Merlijn (2012). “Storytelling, a model of and a model for planning.” Planning Theory 11: 299-318.